I’ve always been fascinated by very, very old things. Fossils. Prehistoric artifacts. Cave paintings and petroglyphs. It’s like reaching out across the expanse of time and touching something that was alive long before what we call history—i.e., our written past.

One of my favorite Twitter feeds is The Ice Age, curated by Jamie Woodward. It’s a succession of images and links and bits of fact, always interesting, and sometimes weirdly apposite to my life in general and this series in particular.

Last September, Prof. Woodward posted an image that made me sit up sharply.

It’s made of mammoth ivory, and is around 35,000 years old. Someone in the feed referred to it as a “stallion,” but it’s not. The neck is too refined, and the shape of the belly is quite round. It is, perhaps, a mare, and perhaps a pregnant one.

And she looks just like this.

That’s a two-year-old filly, photographed in 2001. Many millennia after the ivory horse was carved. But the same arch of the neck. The same curve of the barrel. The same sense of power and presence. But living, and contemporary.

She’s still out there. Older now, of course. Gone as white as ivory, because she’s a grey, and grey horses turn white as they mature. But still all Mare.

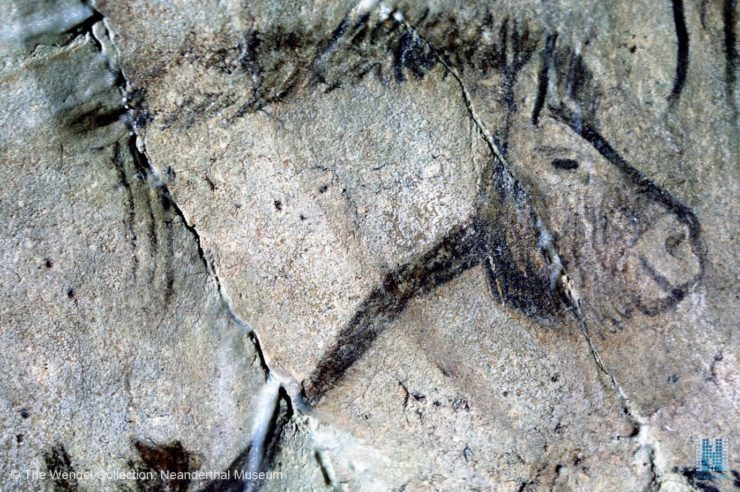

More recently—just a couple of weeks ago—Prof. Woodward posted another striking image (credited to Heinrich Wendel). It’s much younger, between ten and twenty thousand years old, and it was drawn on a cave wall, by firelight, for reasons we don’t know and can only guess. It considerably predates the domestication of the horse—as far as we know—and yet the artist, whoever they were, had really looked at the horse. They had the proportions right. They showed the shaggy hairs around the jaw—maybe winter coat; maybe horses then were just that hairy, like some modern ponies. The ears are up, the nostrils a little flared, the eyes dark and deep. There’s a hint of human expression in the eyebrows and the smile—but horses can be very expressive, and their eyebrows do lift and their lips can turn up.

This artist paid attention. The horse looks out at us across the centuries, and it’s a real horse. It’s alive, as the artist remembered it; because it’s rather unlikely the horse could have been brought into the cave to be drawn from life. Horses do not like confined spaces at the best of times, and horses in that age had never been bred for submission to humans.

That happened much later. Maybe around 6500 BCE, maybe a millennium later. Herds for milk and meat came first; driving and riding, centuries after that, somewhere around 3500 BCE. With the wheel came the chariot, and horses and domesticated donkeys to pull it. And somewhere in there, some enterprising person managed to get a horse to accept being ridden, and then figured out steering and brakes and some form of padding and eventually a saddle and very eventually stirrups.

What also happened, with domestication, was breeding for specific traits. Now that we can learn so much from DNA, there are some genuine surprises popping out in the news. One that got a lot of traction last spring was a study of Scythian horses—a larger group of stallions from one grave dated around 300 BCE, two about 400 years older, and one mare from around 2100 BCE.

The study expected to find in the largest grave what they would find in a more modern excavation: that all the stallions were closely related. But in fact only two were. There was no inbreeding, and no sign of the kind of breeding that’s been done in recent centuries, focusing on a very few stallions and excluding the rest from the gene pool. “Keep the best, geld the rest.”

The Scythians went in another direction—from the evidence, allowing horses to breed as they would in the wild, with stallions driving off their sons and not breeding their mothers or sisters or daughters, but leaving those to secondary stallions. No inbreeding. No line-breeding. No emphasis on specific individuals.

And yet they appear to have bred for specific traits. Sturdy forelegs. Speed—the same gene that gives modern Thoroughbreds their advantage in a race. A gene for retaining water, which the study speculates has to do with breeding mares for milk production. And color: the horses were cream, spotted, black, bay, chestnut.

As a sometime breeder of horses, whose own breed is tiny (fewer than 5000 in the world), I salute these breeders. Our own genetics are surprisingly diverse for the small size of the gene pool, with eight available stallion lines and twenty-plus mare lines and the strong discouragement of inbreeding and line-breeding, but we’re still constrained by something that happened somewhere between ancient Scythia and the modern age, and that is the adage I quoted above, the belief in restricting male lines to a few quality individuals. Quality being determined by whatever the breeders wanted it to be, all too often as specific as color, head shape, foot size, or a particular type of musculature.

And that way lies trouble. Narrowing the gene pool increases the likelihood of genetic problems. If a single stallion is in vogue and everyone breeds to him because of what he offers—speed, color, muscles, whatever—then that cuts out numerous other genetic combinations. And if the stallion’s appeal stems from a particular set of genes, or even a specific mutation, the consequences can be devastating.

That happened to the American Quarter Horse a couple of decades ago. A stallion named Impressive was a huge show winner. The trait in which he excelled was extreme, body-builder musculature. It did not become apparent until significant numbers of mares had been bred to him and then those offspring had been bred to each other, that those huge bulging muscles were the result of a mutation that caused the horse’s muscles to twitch constantly—a disease called Equine Hyperkalemic Periodic Paralysis, or HYPP, also called Impressive Syndrome, because every case traced to that one horse. The only way to be sure a horse does not succumb to the disease is to determine by genetic testing that the horse does not have a copy of the gene, and to exclude all horses with the gene from the gene pool.

Huge mess. Huge, huge mess, with millions of dollars invested in show winners who won because of their big muscles, but who might become incapacitated or die at any time. The fight to mandate testing, and then to bar HYPP-positive horses from being bred, was still going on the last I looked. Because of one stallion, and a breeding ethos that focused narrowly on a single exceptional individual.

Somehow the Scythians knew to avoid this, or else simply did not conceive of breeding related horses to each other. It’s not what horses do in their natural state. How that changed, and when that changed, is still being studied. I’ll be very interested to see the results when they’re made public.

There’s more going on with this ongoing study of ancient horse lines, and more coming out, with more surprises still. One of the widely accepted beliefs of equine science has been that while nearly all current “wild” horses are in fact feral, descended from domesticated animals, one wild subspecies still remains: the Przewalski’s horse. Domestic horses, the theory goes, are descended from the Botai horses of central Asia—in or around what is now Kazakhstan.

But genetic analysis has demonstrated that this is almost completely not true. Modern horses share no more than 3% of their genetic material with the Botai horses—but the Przewalski’s horse is a descendant of these horses. Which means that there are no horses left from any wild population. All living horses are the descendants of domesticated horses, though we don’t know (yet) where the majority of them come from.

What’s even more startling is that the Botai horses carried the gene for leopard spotting, now seen in the American Appaloosa and the European Knabstrupper. Their feral descendants lost it, probably (as the article says) because it comes along with a gene for night blindness. It appears the Botai people selected for it.

Now we’re left to wonder where all our modern horses came from, and how and when the wild populations died out. As for why, I’m afraid we can guess: either incorporated into domestic herds or hunted into extinction—as seems to have happened to the latter in North America. Large, nomadic animals are all too likely to get in the way of human expansion, and an animal as useful as the horse would have to either assimilate or vanish.

What all this means for us now is that we’re starting to appreciate the value of diversity and the need for broader gene pools in our domestic animals. We’ve concentrated them too much, to the detriment of our animals’ health and functionality. Where breeders were encouraged to inbreed and line-breed, many are now being advised to outcross as much as possible. That’s not very much, unfortunately. But every little bit helps.

Top image: Lascaux cave paintings; photo by Patrick Janicek.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks by Book View Cafe. She’s even written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. Her most recent short novel, Dragons in the Earth, features a herd of magical horses, and her space opera, Forgotten Suns, features both terrestrial horses and an alien horselike species (and space whales!). She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.